Home » Posts tagged 'Tariffs' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: Tariffs

How a Tiny Tariff Could Change America

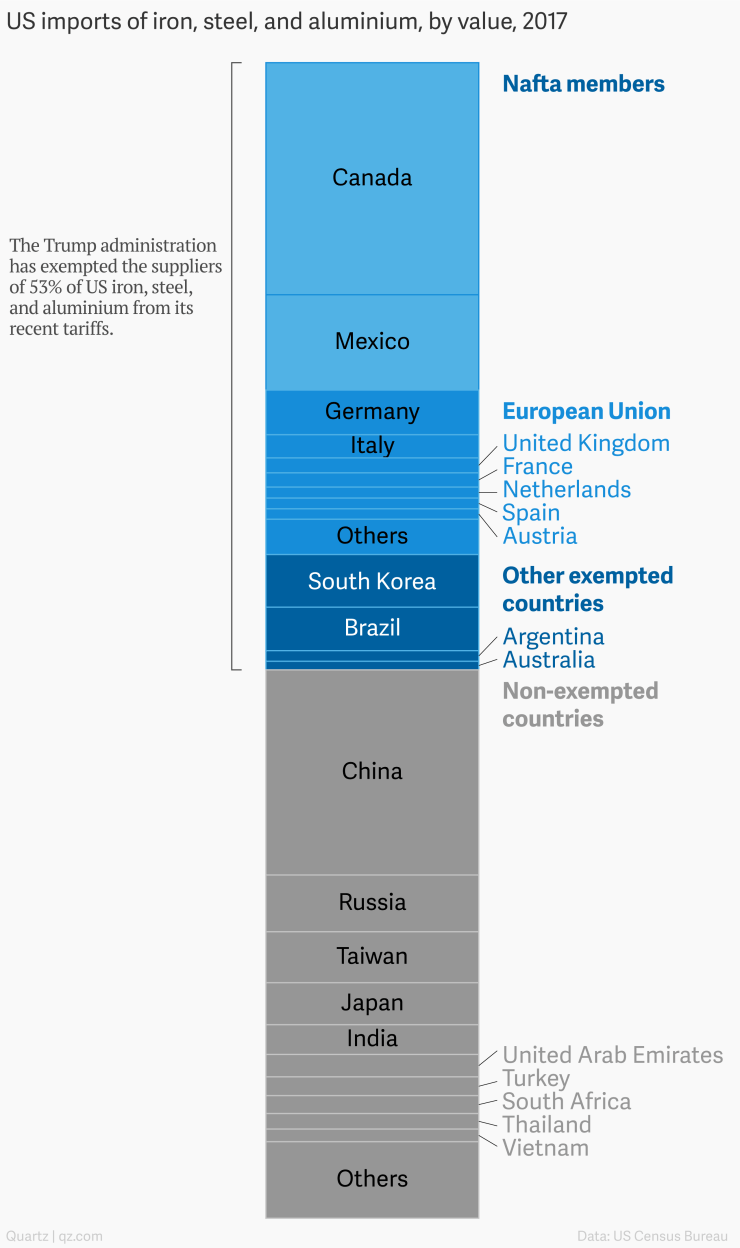

As the debate heats up over President Trump’s 25 per cent steel tariffs and 10 per cent aluminum tariffs (some countries are exempted by Presidential Order) it’s interesting to look at other scenarios that might play out better for the United States — and for other countries too.

First, let’s look at the scale of the American trade deficit problem, then we can compare different methods to adjust trade flows to help the United States avoid a projected $880 billion trade deficit with the rest of the world by FY 2019. No country, not even the mighty United States of America can withstand annual trade deficits of that magnitude.

At the moment, America’s biggest trade deficit is with China ($215 billion/yr) followed by Japan ($68 billion/yr) and Mexico ($65 billion/yr) while many other countries run double-digit trade deficits against the United States. In totality, such trade deficits are simply unsustainable for the U.S. and President Trump is right to address the issue, however, there’s always more than one way to accomplish a thing.

U.S. Imports: The timeline shows the total value of international U.S. imports of goods and services from 2000 to 2017. In 2017, the total value of international U.S. imports of goods and services amounted to 2.9 trillion U.S. dollars. Image courtesy of Statista.

U.S. Exports: The timeline shows the total value of international U.S. exports of goods and services from 2000 to 2017. In 2017, the total value of international U.S. exports of goods and services amounted to 2.33 trillion U.S. dollars. Image courtesy of Statista

The Nature of the Problem

America’s trade deficit is an astonishingly simple problem that has developed over four decades — because when a thing evolves without proper guidance and oversight, eventually it becomes the thing that eats you — which is what’s happening to the United States in the 21st century.

Because policymakers allowed this monster to grow, it means the U.S. will import $557 billion more than it exports in 2017, instead of maintaining a normal balance of trade like other countries. And 2018 is projected to produce an $880 billion trade deficit for the United States, with a $1 trillion trade deficit sure to arrive by FY 2020 if action isn’t taken to address this catastrophe.

President Trump claims that the American trade negotiators of previous decades were ‘weak’ and got ‘out-negotiated’ by other countries and blames them for the present (uncomfortable) moment. But that isn’t accurate. However, it plays well with voters, and media outlets especially, thank Donald Trump for that characterization.

What happened is that America opened trade with China and other developing nations beginning in earnest in 1974, allowing generous trading terms to add impetus to America’s trade liberalisation goals. American policymakers assumed that once those developing nations got a real economy going, citizens of those countries would then purchase billions of dollars of American goods and the gamble would pay off handsomely. And therein lies the problem. Not every country reciprocated America’s largesse.

China, Japan, and other countries simply grabbed the Americans by their largesse and began exporting evermore billions of dollars worth of goods and services to America without buying much of anything from the United States.

Note: In Japan’s favour, the country’s carmakers aggressively lobbied Washington to be allowed to build factories throughout the United States and Canada which provided thousands of jobs across North America every year since 1987. Also, Japan bought hundreds of billions of dollars worth of U.S. Treasury Bills to help maintain the American economy. These wise actions ameliorated the concerns of U.S. legislators about Japan’s trade imbalance with the United States from 1987-2017.

Which should qualify Japan for a ‘Free Pass’ from all steel and aluminum tariffs IMHO, as Japan was led to believe by American legislators that their actions neatly covered any trade negatives in the U.S. / Japan relationship.

Asleep at the Switch?

If someone in America had been ‘on this’ it would have never gone this far. But someone in America was asleep at the switch and that’s why we are where we are, in 2018.

The problem, therefore, isn’t that America got ‘out-negotiated’. The problem is that certain countries took advantage of America’s generous trade terms but were reluctant to accept imports from the United States.

Whoever was in charge of international trade in the U.S. from 1990 until 2018 should have Fried in Hell for not raising the alarm and writing some appropriate ‘fair trade’ legislation that would serve as a check and balance against such one-sided trade flows.

The $10 Billion Tripwire Method

Countries that run trade surpluses of less than $10 billion/yr with the U.S. shouldn’t face American tariffs as those numbers typically go up and down many times over the course of a decade and can even reverse direction to America’s benefit, and in any case, rarely become double-digit or triple-digit trade imbalances.

But once a country hits the $10 billion trade deficit threshold with the United States, it should trigger alarm bells from Alaska to Maine and appropriate tariffs (like Donald Trump’s high-ish steel and aluminum tariffs) should automatically apply on exports to the U.S. from any country that surpasses the $10 billion tripwire.

It’s such a good idea that every country should do it.

The 5% Method

If the United States charged a truly nominal 5 per cent tariff on every foreign good and service it would raise $150 billion per year which is a substantial amount of money for any country, even a superpower.

The U.S. could use that money to subsidize American companies hit hard by low-priced imports since 1990 (maybe by providing financing assistance to allow them to build newer, more energy-efficient factories for example), to improve transportation corridors throughout the country (especially near America’s seaports), to upgrade the actual port facilities to allow for faster and more efficient throughputs of American products being shipped overseas, and to enhance security at every single U.S. port of entry.

This too, is such a good idea that every country should do it.

Balancing an Unbalanced Equation

If the United States adds a nominal 5% tariff to all foreign goods and services, and then on top of that tariff penalizes (with industry-specific tariffs) only the countries that run more than $10 billion trade deficits with the U.S., the entire problem will be solved within 5 years and the American economy will boom like never before.

Also, in a booming U.S. economy, countries like China will find that orders from America will increase and any losses felt now will be recovered within a year or two.

‘Corrective’ Tariffs Need to Replace ‘Punitive’ Tariffs

The only way to conduct international trade is with respect, with proper checks and balances, with mild tariffs designed to make corrections to uneven trade flows resulting from poor policy in previous decades, and none of it needs to be confrontational or nasty.

For the sake of its hard-working citizens, American policymakers must address these imbalances in a businesslike way — not to punish other countries — but rather, to ensure that every country that trades with the U.S. is doing so in a fair and transparent manner.

To Xi With Love, from Donald Trump

President Xi Jinping of China was awarded a second term in office by the Communist Central Committee of China just days ago (and doubly rewarded because term limits no longer apply to Mr. Jinping) has received communication from the Trump administration that steel exports to the United States will now face a 25 per cent tariff and aluminum exports to the United States from China will have a 10 per cent tariff added.

The tariffs against China and selected other countries are scheduled to go into effect March 24, 2018.

President Donald Trump of the United States says there is a huge and historic trade imbalance between the U.S. and China and is using tariffs to counter that imbalance which has been pegged between 374 billion and 511 billion dollars, depending upon how those figures are calculated.

Further, Mr. Trump has asked President Xi to submit a plan to lower the trade deficit with the United States by 100 billion dollars as soon as possible.

Which Countries are Exempt from the Tariffs that Begin on March 24, 2018?

China has Responded to Trump’s Tariffs with Tariffs Against U.S. Goods

In response to Mr. Trump’s tariffs, China’s leader Mr. Jinping has responded with some mild tariffs against the United States.

China’s ambassador to Washington, Cui Tiankai, said on Thursday that Beijing would retaliate against those tariffs on about $60 billion of Chinese goods.

“We do not want a trade war with the United States or with anybody else, but we are not afraid of it,” Mr. Cui said, according to Xinhua, the official news agency. “If somebody tries to impose a trade war upon us, we will fight. We will do whatever we can to defend the legitimate interests.”

The $3 billion worth of goods that Beijing plans to penalize represent just about 2 percent of U.S. exports to China, which amounted to $130 billion last year, according to Chad Bown, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“It’s not devastating economically by any stretch, but it’s certainly going to hurt those interests in the United States that are trying to export,” Mr. Bown said. He pointed out that the retaliation by China sends “a negative signal, that they are not seeking to de-escalate things.” — excerpt from the New York Times

All in All, Not a Trade War

Except that two superpowers are involved (which makes for great theatre) it’s not much of a trade war.

In fact, the Trump tariffs against Chinese steel (China supplies only 2% of U.S. steel) and Chinese aluminum (supplying less than 1% of U.S. aluminum) won’t amount to mega-billions of dollars.

Still, Trump has set the tone that countries that export to, and run huge trade deficits with the United States, will be addressed at the tariff level. Back in the old days getting your way in trade disputes was done by so-called ‘Gunboat diplomacy’ instead of the much softer tariff approach.

Thank goodness we’ve matured as a species!

Further tariffs may be levied on China and other countries by the Trump White House as the president seeks to balance America’s huge trade deficit across many nations that export to the United States.

The reason China has been singled-out is that it runs triple digit trade imbalances with America — not because anyone in the Trump White House has any particular enthusiasm to embarrass or anger China.

And although Donald Trump did make the numbers known to the public and did spend some time justifying his new tariff policy, it looks like the president sincerely wants a solution to the existing problem and doesn’t want a situation that escalates without resolution. We know that because he chose his words and his tweets very carefully.

Light at the End of the Tunnel?

What’s really at stake here is the long-term relationship between America and her trading partners.

China, Canada, Mexico, and the European Union are America’s largest trading relationships and in order for the United States to succeed it can’t allow huge trade deficits with every country it does business with.

If every country in the world ran a microscopic trade deficit of only 10 billion dollars with America, the U.S. trade imbalance would total 2 trillion dollars!

“To put that in perspective, if you stacked 1.9 trillion $1 bills on top of each other, the pile would reach about half way to the Moon.” — CNN

Not even the mighty United States of America can survive trade deficits of that magnitude.

China’s trade imbalance of ($374 billion to $511 billion in 2017, depending how you calculate it) is simply unsustainable for America, as are the double-digit trade deficits of several other countries.

This chart (unfortunately, from 2016) shows only the countries that have double or triple-digit trade imbalances with the United States (in millions of dollars)

Note: The European Union trade imbalance with the United States is 146 billion dollars, but some of those EU nations are also listed separately in this chart.

The Best Case Scenario?

As the tariffs go into effect, the best we can hope is that cooler heads prevail and that both the American and Chinese tariffs are seen as simple corrections to segments of the economy long neglected by policymakers on both sides of the Pacific.

Several countries that export steel and aluminum to the U.S. are exempt from the tariffs so American consumers will see very little change in prices. Consumers in China may see small price increases in certain foods that are imported from the United States.

The entire situation is an example that we should be mindful of our free trade privileges with other countries, neither exploiting them too much nor allowing ourselves to be exploited by them. Triple and double-digit trade imbalances don’t ‘just happen’ overnight! And they should be mindful of their free trade privileges with us.

If this in any way presages a shift toward fair trading rules between all nations — as opposed to unrestricted free trade — it means that international trade will be much more sustainable, and frankly, more easily welcomed by every country in the future.

Let’s hope this marks the beginning of the ‘Trump Doctrine of Fair Trade’ between nations.

Transforming Britain’s Trade Partnerships

by John Brian Shannon | July 25, 2016

Every day of the year, we teach others how to treat us.

If we consistently demonstrate that we’re reliable, we teach others to trust us. If we demonstrate that we’re untrustworthy, we teach others to avoid us.

And so it is with nations; By virtue of their policies and procedures and by their other actions, we teach the leaders of other nations and their corporations how to treat us, how to deal with us, or give them reasons to avoid us.

Pretty simple stuff. We learned this in kindergarten.

But sometimes we get so busy working in our business we forget to work on our business, and that message can lose place.

In the interdependent world of the 21st-century, the highest priority for British Prime Minister Theresa May and her ministers must be to work on our business and not get wrapped up in the daily routine, and thereby lose place.

The government of Theresa May is off to a good start and it’s too early to draw conclusions about her future economic policy, but governments of the past have ranged from inspired to dreadful in regards to steering Britain’s economy.

The United Kingdom is the 5th-largest economy on the planet. Let’s not lose that.

Partnership

We need to trade with stable regimes, it’s better for market certainty. They want us to be economically certain. We need them to be economically certain. In fact, economic uncertainty is our enemy and theirs.

Therefore, interdependence and symbiotic relationships will work best for us and for our trade partners.

If we ensure that engaging in trade with Britain always works to the advantage of our trade partners, we will teach them that more trade with us is their goal.

In this way, our trade partners become our best sales and marketing force. Handy, that.

Using Import Tariffs as Revenue Stream

Minimal standardized tariffs can offset government budget imbalances and balance of trade issues — and that applies not only to Britain, but also to it’s trading partners.

As a general rule, Britain should engage in free trade with every country and charge a standardized 5% tariff on every good that is shipped to the UK. And all countries that trade with Britain should likewise institute a harmonized 5% tariff.

Q: Why would Britain want foreign governments to charge a 5% tariff on British goods?

A: Each $1 billion dollars of British export earns that foreign government $50 million dollars in (import) tariff revenue.

But why would foreign governments shoot for British exports of only $1 billion per year / $50 million tariff revenue when those governments could collect $600 million in tariff revenue on $12 billion of exports from Britain?

Or ten times that amount. Let’s hope.

Easy Money

Therefore, the higher the gross total value of imports arriving from Britain, the more dependent the foreign government will become on that revenue. Which means they won’t want anything interfering with that simple and easy tariff revenue stream!

“Can you please continue to export to my country?”

“Why yes… yes we can.”

Anytime the UK government wants to increase exports, all it must do is ask each foreign government representative this sort of question:

“How would you like to be responsible for bringing home $600 million per year in tariff revenue, instead of the present $50 million per year?”

It’s so easy when they do the work for you…

Transformation

By asking for the cooperation of our trade partners in this manner, not only will UK exports realize a manufacturing boom, but the partner nation will see a tariff revenue boom — and that’s interdependence taken to the next level.

Symbiotic trade relationships become the path to prosperity for both partners.

If Britain does this, and does it well, every country in the world will become a highly motivated salesforce for British goods — your trade partners are practically marketing Britain’s manufacturing sector for you.

As the price of each imported item increases by 5%, it will spur domestic demand on account of UK-produced goods not having a price rise due to a 5% tariff.

In that way, domestic production will increase, which has several positive influences in the overall British economy; UK-produced goods will be incrementally cheaper in comparison to imported goods, increasing consumer demand for UK-produced goods, causing UK manufacturing sector unemployment rates to fall, and consequently the government will lower it’s unemployment insurance expenditures and receive higher income and sales tax revenue from those now-working citizens.

And that’s not all

In addition to those positives; The UK government gets a new revenue source to augment it’s spending programmes. In the UK, this translates into more funding for Britain’s highly-ranked National Health Service (NHS) and makes deficit-reduction a reality for the Exchequer.

Since the global financial crisis, the UK government has in addition to running a mild austerity programme, also run high budget deficits (8.5%) which simply accumulate as government debt — and that’s the last thing the country needs as the UK’s debt-to-GDP was already too high prior to the financial crisis of 2008.

Global Debt Clock for Britain 2015. Image courtesy of The Economist’s Economic Intelligence Unit.

But with billions in tariff revenue helping to fund UK government operations, not only would deficits disappear and high public debt taper, there would be enough revenue left over to fund the ‘shovel-ready’ infrastructure projects that are unemployment-reducers, job-creators, and income tax generators for the country.

In economics, that is known as a virtuous circle. Which is a very wonderful thing.

Economists win Nobel Peace Prizes for engineering virtuous circles. Yes, it is that big a deal.

Investment

Tariffs should be seen by Britain and it’s trading partners as revenue generators.

Revenue from tariffs can fund deficit elimination, debt repayment, infrastructure and job creation or whatever gives the UK economy the best bang for the buck at that time.

Growing economies attract a lot of attention — the good kind. And every investor wants to invest in a winner.

By designing our economic fundamentals to mesh with the present economic moment, the UK could enjoy an almost unprecedented economic boom courtesy of the virtuous circles deliberately engineered into Britain’s economy.

Delivering on that goal should be our highest priority.